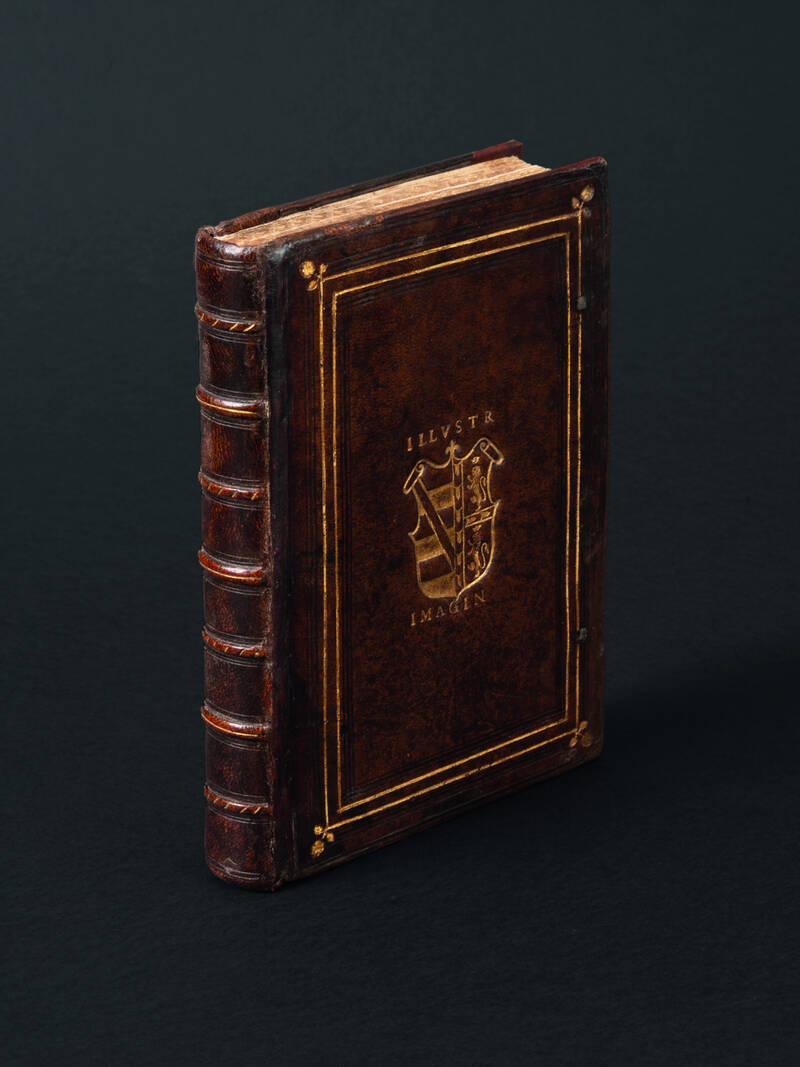

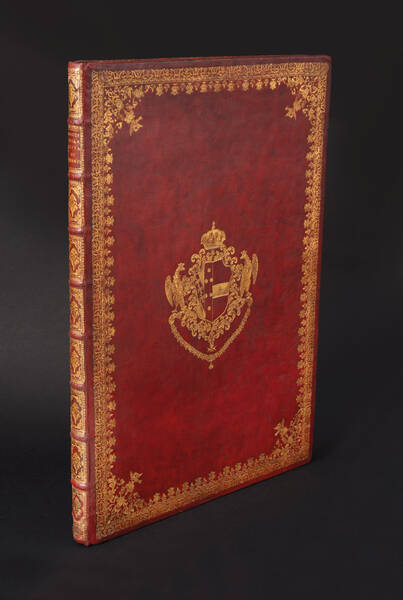

FULVIO, Andrea. Illustrium imagines.

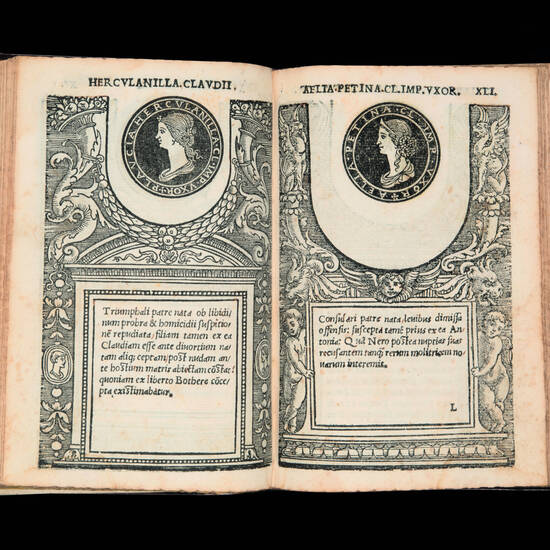

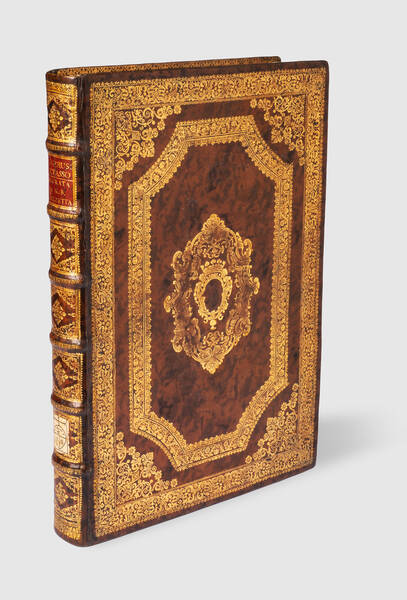

Rome, Jacopo Mazzocchi., 15 November 1517Octavo (155 x 103 mm.), 120 leaves, title within a woodcut border in the form of a tablet or a tomb, 204 medallion portraits, woodcut printer's device on last page. ‘Each portrait is set in the space in the upper part of a border block which contains the text set in a second space below. The borders are designed to resemble antique monuments with the text in the position of a carved inscription. The portraits white-on-black are taken from coins and medals in Mazzocchi's own collection and the cuts are ascribed to Ugo da Carpi'. (Mortimer) A few spots, light foxing, ancient Greek marginal annotations in the first leaves, spine restored, but a fine copy in Roman brown morocco, ca. 1540, frame of double gilt fillets flanked by multiple blind fillets, gilt fleuron at outer angles, in center large gilt stamp of Massimo family arms and the inscription ·ILLUSTR·IMAGIN in gilt, spine with raised bands, edges gilt with two rows of dots gauffered around sides. The Massimo were one of the oldest aristocratic families in Rome. The binding boasts their family arms, specifically suggested by Hobson as the arms of Antonio di Pietro Massimo (d. 1561), or alternatively Lelio Massimo, marchese di Santa Prassede. The mysterious Massimo bibliophile of the 1530s onwards has not yet been identified. This is one of thirteen known sixteenth-century bindings adorned with Massimo arms. (Tammaro de Marinis, La Legatura artistica in Italia nei secoli XV e XVI, Florence 1960, no. 622)

First edition of the earliest collection of reproductions of ancient coins to be printed; the first illustrated numismatic book and the beginning of modern numismatics. “The Illustrium imagines presents a history of Rome from its establishment down to the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III, presented as a series of summary epitaphs accompanied by an image of the individual in coin format.” (Brian Madigan) “Despite the interest in numismatic taken by the humanists, it was only in 1517 that what could be called a collection of reproductions of classical coins first appeared in print, the Illustrium imagines, commonly attributed to Andrea Fulvio. Reproductions they were, but only up to a certain point, since, though the images appearing on Roman coins were faithfully reproduced, the same cannot be said for their inscriptions. The real aim of the Illustrium imagines was not, however, strictly numismatic, for it really set out to furnish an iconographic repertory, though derived whenever possible from numismatic sources. Thus each person included in it has a medallion with his or her portrait and a short biographical account underneath it, the series starting with the god Janus and ending with the Medieval Emperor Conrad I. Inevitably most of the ‘portraits' belonging to the republican or the medieval period are fictitious. On the other hand, those of the imperial age were derived from contemporary coins, and when a coin was not available, the space for the medallion was generally left blank. Not surprisingly, the Illustrium imagines enjoyed a European reputation. Reprinted in Lyons in 1524, it was imitated, one year later, in the Imperatorum Romanorum libellus of Johann Huttich, a work which was in its turn reprinted several times. There is no doubt that it was from the Illustrium imagines, a collection which expressed the antiquarian enthusiasm of Roman humanism during the pontificate of Pope Leo X, that the numerous iconographic repertories of the sixteenth and seventeenth century derive. It is equally clear that this work marked the culmination and also the end of what may be called the first period of numismatic studies. It was only a few decades later that a more scientific approach to the actual study of coins really began. During the first period, numismatic studies were considered from only three angles. There was the iconographic element; there was the investigation as to the value which ancient coins had in term of modern money; and there was the use of coins as pieces of evidence, which could be brought to throw light on some obscure historical or antiquarian problem.” (Roberto Weiss, The study of ancient numismatic during the Renaissence (1313-1517). In The Numismatic Chronicle, vol. 8, 1968).

Adams F-1156; Ascarelli Mazzocchi 116; Brunet II: 1423 Cicognara 2851; Mortimer Italian 203; Sander I:2978.

Other Books

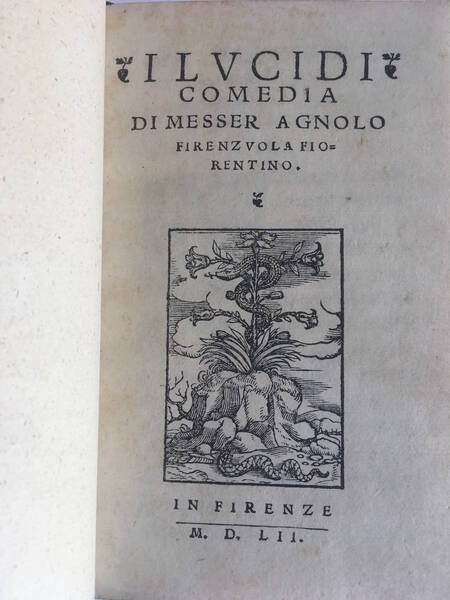

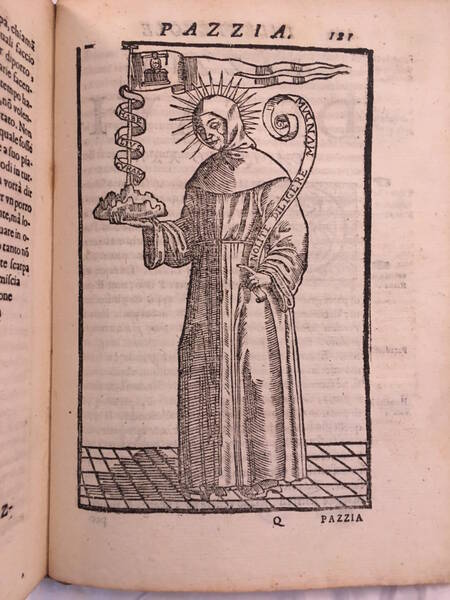

SPELTA, Antonio Maria

La saggia pazzia, fonte d’allegrezza, madre de’ piaceri, regina de’ belli humori.

€ 2.000![[De Architectura libri decem], M. Vitruuius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula vt iam legi et intelligi possit. [De Architectura libri decem], M. Vitruuius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula vt iam legi et intelligi possit.](https://www.medariquier.com/typo3temp/pics/b57e48f107.jpg)

VITRUVIUS POLLIO, Marcus

[De Architectura libri decem], M. Vitruuius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula vt iam legi et intelligi possit.

SOLD OUT

TASSO, Torquato

La Gerusalemme liberata di Torquato Tasso con le figure di Giambatista Piazzetta, alla Sacra Real Maestà di Maria Teresa d’Austria, regina...

€ 18.000

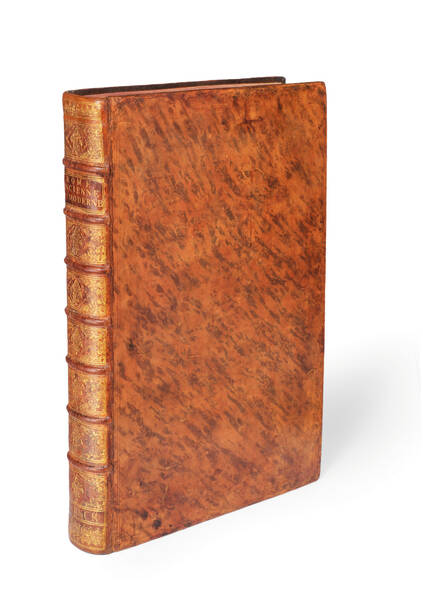

BARBAULT, Jean

Les plus beaux monuments de Rome ancienne.– Les plus beaux edifices de Rome moderne.

SOLD OUT

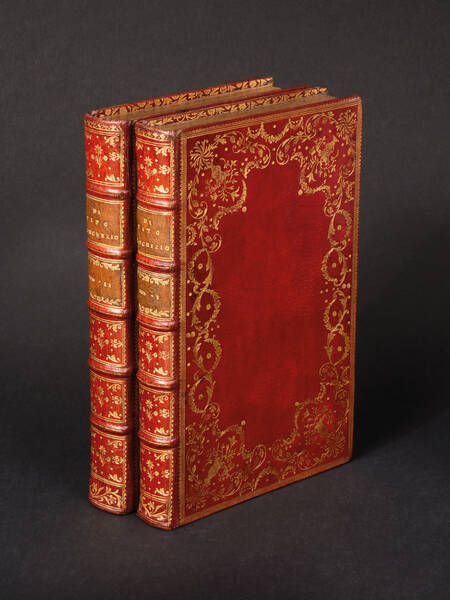

LUCRETIUS, Titus Carus

Della natura delle cose libri sei, tradotti dal Latino in Italiano da Alessandro Marchetti. Dati nuovamente in luce da Francesco Gerbault.

€ 7.000

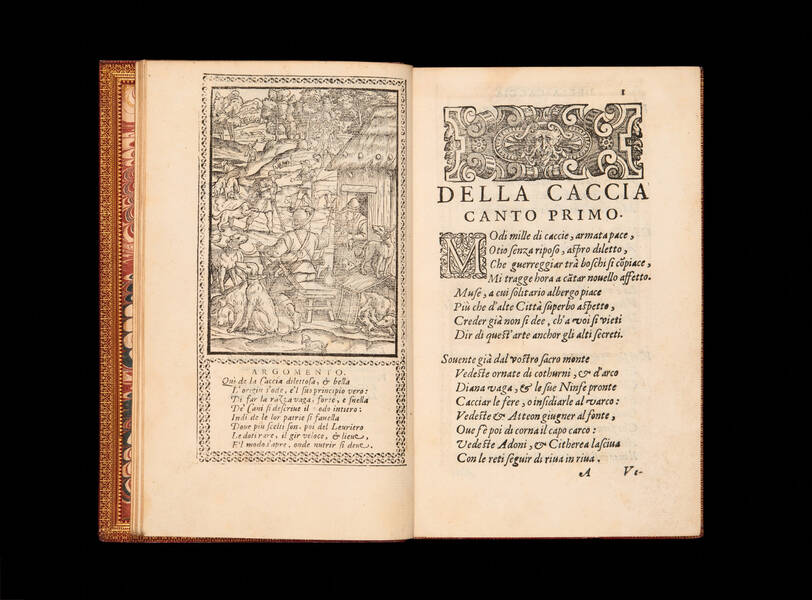

VALVASONE, Erasmo da

Della caccia poema del signor Erasmo di Valuasone. All'ill. signor Cesare di Valuasone suo nepote. Con gli argomenti a ciascun canto del sig. Gio....

€ 3.500

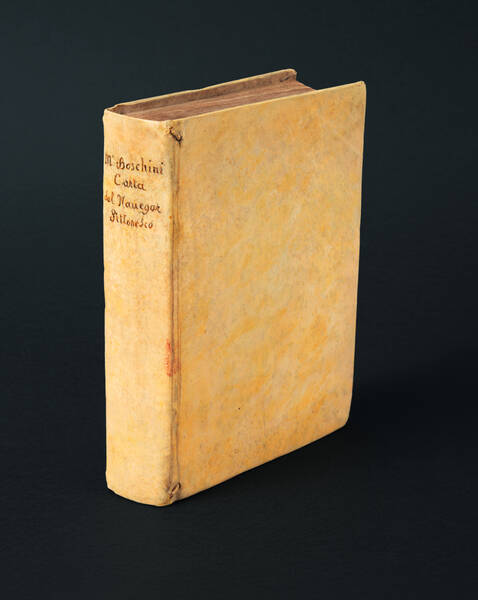

BOSCHINI, Marco

La carta del nauegar pitoresco dialogo tra vn senator venetian deletante, e vn professor de pitura, soto nome d'ecelenza, e de compare. Comparti' in...

€ 7.000

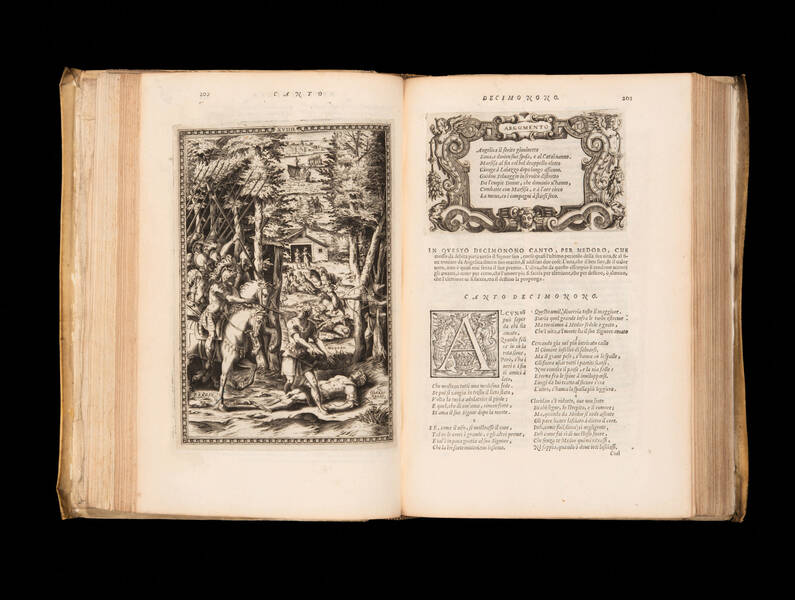

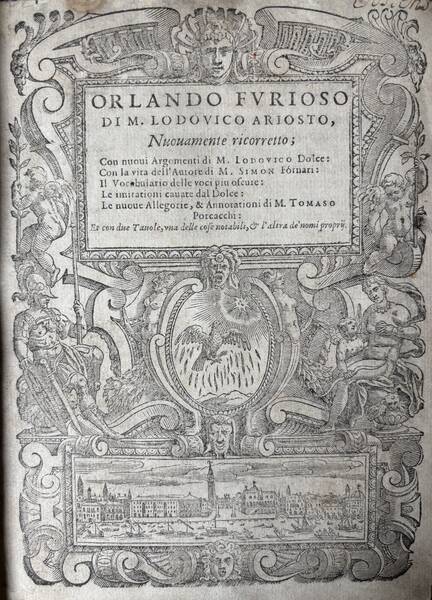

ARIOSTO, Ludovico

Orlando Furioso di M. Lodovico Ariosto, nuovamente ricorretto; con nuovi argomenti di M. Lodovico Dolce: con la vita dell'autore di M. Simon Fornari:...

€ 3.000

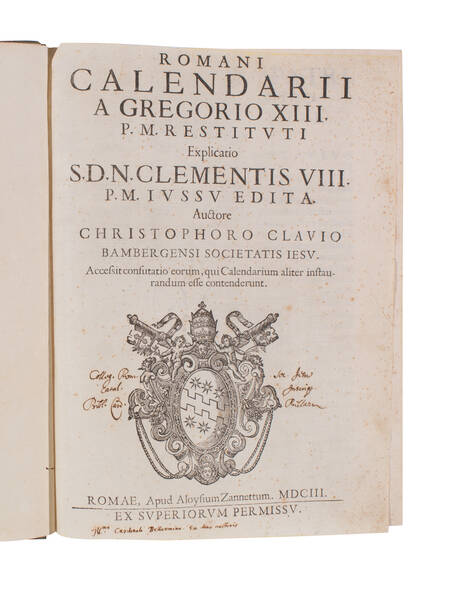

CLAVIUS, Christoph

Romani calendarii a Gregorio XIII. P.M. restituti Explicatio S.D.N. Clementis VIII. P.M. iussu edita.

SOLD OUT

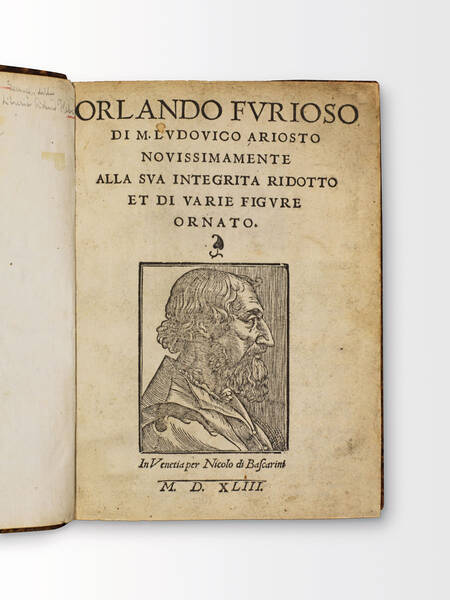

ARIOSTO, Ludovico

Orlando Furioso di M. Ludovico Ariosto novissimamente alla sua integrità ridotto et di varie figure ornato.

€ 12.000

ZOCCHI, Giuseppe

Scelta di XXIV vedute delle principali contrade, piazze, chiese, e palazzi della citta di Firenze.

€ 45.000

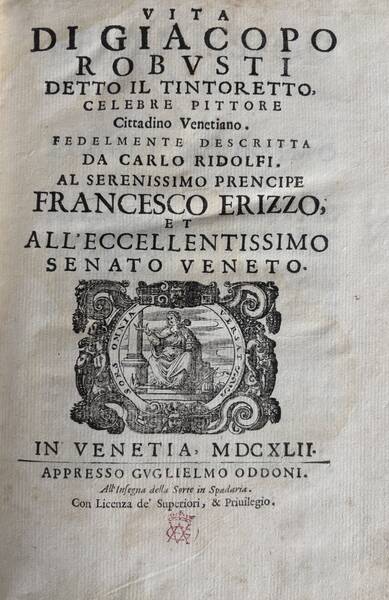

RIDOLFI, Carlo

Vita di Giacopo Robusti detto il Tintoretto, celebre pittore, cittadino venetiano.

€ 2.500

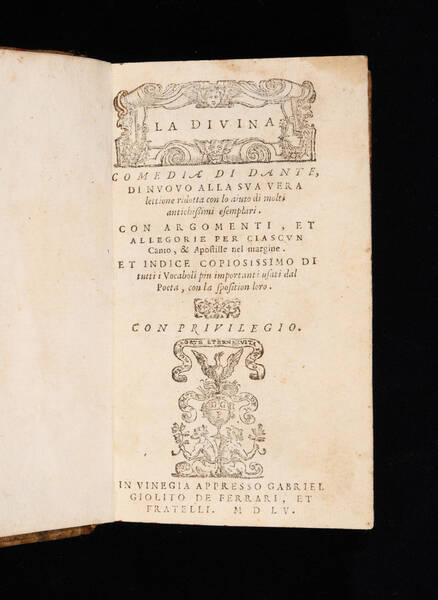

ALIGHIERI, DANTE

La Divina Comedia Di Dante, di nuouo alla sua vera lettione ridotta con loaiuto di molti antichissimi esemplari. Con argomenti, et allegorie per...

SOLD OUT

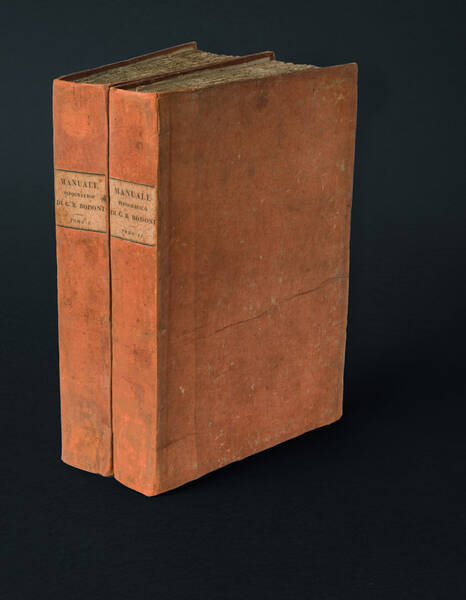

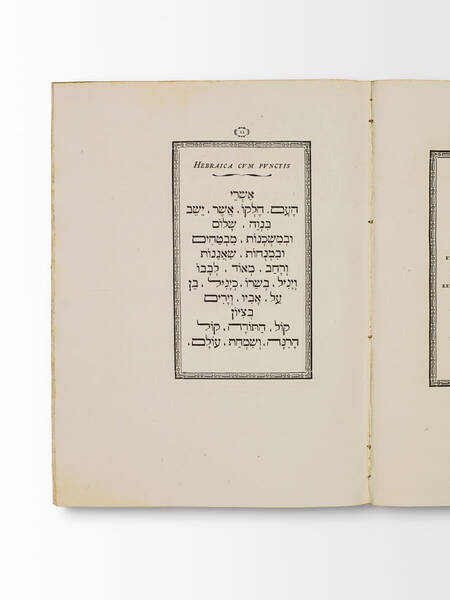

[BODONI]

Pel solenne battesimo di S.A.R. Ludovico Principe primogenito di Parma tenuto al sacro fonte da Sua Maestà Cristianissima e dalla Reale Principessa...

€ 6.000MEDA RIQUIER rare books ltd.

4 Bury Street St James's

SW1Y 6AB London

Phone +44 (0) 7770457377

info@medariquier.com