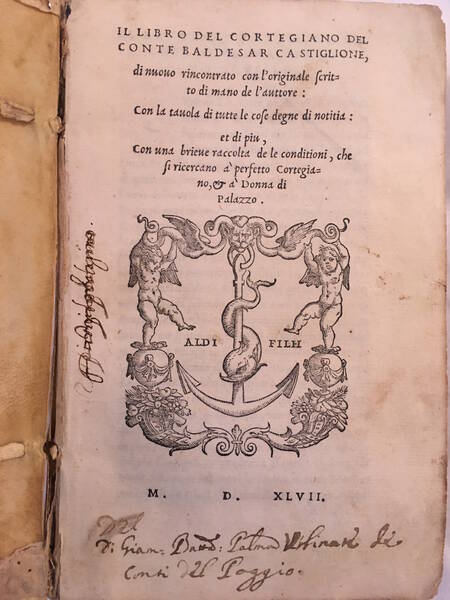

VITRUVIUS POLLIO, Marcus. [De Architectura libri decem], M. Vitruuius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula vt iam legi et intelligi possit.

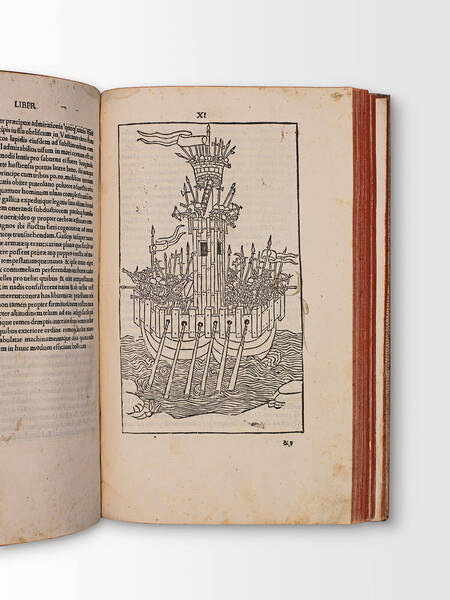

Venice, Giovanni Tacuino da Trino., 1511.Folio (310 X 206 mm.), [4], 110, [9] leaves without the final blank leaf, and Tacuino's orb and cross device on penultimate leaf. Roman type, a few words in Greek, shoulder notes, index at end in triple column. “Title-border with dolphins, a continuous design in four parts. There are a number of variations on this dolphins composition, and if the Tacuino border is the original, it was one of the most influential pieces of ornamentation of the sixteenth century. […] One hundred fhirty-six woodcuts, 52 x 128 mm. to 230 x132 mm. These are diagrams, plans, architectural details and full illustration of machinery in use. The block on leaf G8 verso is printed upside down […] In the illustration of the mill on leaf H5 verso the two sacks on the floor have Tacuino's orb and cross device with the initials ZT”. (Mortimer) Minimal restoration on the upper right corner of the first two leave, a long bibliography note on front fly-leaf, an ancient signature on title-page, a few small spots, overall a very good copy entirely règle, recased in a restored contemporary limp vellum binding.

First illustrated edition of Vitruvius, and the first edited by Fra Giovanni Giocondo.

“In 1511 the Venetian publisher Giovanni Tacuino published M. Vitruvius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula ut iam legi et intelligi possit (M. Vitruvius, made purposely more comprehensible than it is usual, thanks to figures and tables, in order it would be possible to read and understand it): it was the first illustrated edition of Vitruvius' De architectura. Fra Giocondo, the architect and humanist from Verona who curated the work, was animated by various interests, which urged him to seek a full understanding of the Vitruvian treaty.

The figure of Fra Giocondo must first of all be examined within the Venetian culture, architecture and politics of the early 1500s: circles with which the friar confronted himself after being named Consilii X Maximus architectus on his return from France. Although the arrival of Fra Giocondo was dictated by reasons of practical urgency, that is to say the worsening of the lagoon's interment, his presence became the keystone for the translation into architecture of the project of renovation of the city (Renovatio Urbis) proper to the cultural elite close to future Doge Andrea Gritti. The architectural result of Giocondo's influence in Venice were the projects that were undertaken in the Rialto area at the beginning of the century, in particular the reconstruction of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, whose layout closely resembled an engraving of the Vitruvius edition.

Cultivating different fields of study and developing a multiplicity of skills, the friar managed to unify in his work the two strands of research where he had achieved most distinguished results until then: on the one hand the antiquarian-philological exploration and on the other the practical-operative execution. Indeed, Fra Giocondo accomplished a more correct Latin text than in previous editions, accompanied by a rich xylographic apparatus - 136 incisions distributed in all ten books - and with the addition of an index that facilitated its understanding, as stated since title. It was a real turning point in Vitruvian studies. On the one hand, thanks to the completion of the text's gaps, the work was addressed to the world of humanists. On the other hand, through the straightforwardness and immediacy of the engravings, it also aimed at an audience with the most genuinely operational needs. For Venice, a city which had barred ancient architecture so far, this was the first act of a transformation that would lead, in a short span of years, to be an international Vitruvian pole, a centre of attraction for amateurs and architects, competitive also compared to Rome.

In the history of the fortune of De architectura, Fra Giocondo's text represented an indispensable turning point, revolutionary for the new type of cognitive and unitary practical interest with which the friar approached Vitruvius: the need to provide a text that would be widely comprehensible and usable brought him to make philologically unorthodox interventions that, however, produced exegeses accepted by later critics. […] A two-fold analysis of the edition of Giovanni Tacuino, which therefore reserves equal dignity and space to the philological and illustrative and didactic aspects, assigns to Giocondo's illustrative apparatus a decisive role for his editorial fortune of the work, as reiterated by the reissues of 1513, 1522 and 1523. The 1511 version of Vitruvius should also be appreciated as an editorial operation, taking into consideration the typographical activity of the publisher Giovanni Tacuino in the field of Venetian culture and publishing activity at the turn of the sixteenth century. This Trino-born printer accomplished a variegated production: alongside the mainly Latin classics, he also prepared works on religious and moral themes. Most probably, the production in the vernacular language, directed at the larger public and without any particular pretensions as to the layout, eventually guaranteed him the economic basis necessary to carry out elaborate productions of classical texts.

The cultural itinerary undertaken by Giocondo in choosing the publisher is in line with an analysis of the political climate that overwhelmed the publishing industry in the years around 1511, with particular reference to Aldo Manutius's activity. Aldo and Giocondo had a close relationship: in November 1508 Manuzio published the Epistulae of Pliny the Younger together with Giulio Ossequente. They were the results of a discovery in the Parisian years of the friar and a collation of texts to which Jiano Lascaris certainly participated, but which could also have involved the French writer Guillaume Budé. This was followed in April 1509 by De Conjuratione Catilinae, for which Aldo used two Parisian codes transmitted by Giocondo and Lascaris, and in 1517 the posthumous edition of the Epigrammata by Martial, also published «Venetijs in aedibus Aldi et Andreae Soceri» Manutius also secured the friar's help after the latter had already left for Rome: to testify it is the letter of 2 August 1514, addressed by Giocondo to Aldo, and discussing with a French Nonius Marcellus the De re rustica and the Cornucopiae, both published in 1513. In the same year, the Commentaries of Caesar, dedicated to Giuliano de' Medici and accompanied by various xylographs, were also brought out. One of them, the Pictura totius Galliae was probably inspired by an ancient manuscript, perhaps the same one that Poggio Bracciolini had seen in Paris.

In the years immediately preceding and following the Vitruvius prints (1509-1512), Manuzio's flourishing company found itself at the mercy of political events which weakened the Serenissima substantially. The battle of Agnadello decided the fate of the war and brought about the ruin of the Venetian mainland state, and the defeat of Bartolomeo d'Alviano, patron of Aldo. The enture printing industry remained entangled in a convulsive regression mechanism: Aldo abandoned Venice, leaving his company in the hands of Andrea Torresani, while about twenty other establishments still in business were producing only about fifty editions a year. On the one hand, this explains why Giocondo did not use the establishment of his friend and collaborator Aldo for the printing of his Vitruvius, on the other hand these events clarify the importance which a publishing event of this kind could have, for its author, for the publisher and for the entire city. The printing of the first Vitruvius and its illustration by the person who could be defined as the State architect might in fact be read - with the due proportions - as another sign of Venice's recovery after the War of the League of Cambrai; in the architectural field, indeed, the same could be said about the contemporaneous interventions in the buildings of the Procuratie vecchie in St Mark's Square. The Republic had already identified itself in Giocondo, who ‘could be called the second edificator of Venice' (Scipione Maffei) given his commitment to counteract the interment of the lagoon. In a period of obvious difficulties, thanks to him Venice could now claim the primacy in the edition of a work which obtained an international consensus, as the subsequent editions did show, also because it attempted to reach a vast public without excessive typographic refinements. This may also explain the dedication of the work to Julius II, although devoid of political references: Giocondo, who had shown his political orientation by alerting from France the Venetian Republic about the papacy's conspiracies against the Republic, in 1511 dedicated his Vitruvius to the ‘blessed Julius II Pontifex Maximus'. This may have either been an act of gratitude from a religious to the Pope or the sign of the resumption of cordial relations between Venice and the pontifical seat, after the establishment, in that same year, of the Holy League. When the Vitruvius's edition of 1511 was printed, Giocondo was almost eighty years old. His work mirrored the interests and skills he had matured over a lifetime. […], about his life we know nothing for the first fifty years. This gap on his most formative years represents one of the greatest difficulties in approaching a man who, as already mentioned, displayed over the years an intense activity both in the philological-epigraphic and in the technical-artistic fields. […] These were crucial years because the idea of publishing Vitruvius must have taken shape here: the comparison between the code V. 318 of the National Library of France - probably annotated by Guillaume Budé during the Vitruvian lessons held in Paris - and the Vatican equivalent (Inc. II. 556) with notes by hand from Jano Lascaris, testifies to a work already largely outlined. The incunabula represent an exceptional proof of the team work which helped the 1511 edition come to life. It was the prologue of a story that would be eventually fulfilled in Venice, where Giocondo carried out - again - the purpose of sharing and transmitting knowledge. That purpose characterized him throughout his life and was reaffirmed in the plea to the Council of the Ten: ‘I am offering to teach all what I know to three, four, or how many people this most illustrious Lordship may wish.'” (Francesca Salatin, An Introduction to Fra Giocondo's Vitruvius (1511). https://letteraturaartistica.blogspot.com/2019/05/vitruvius-giocondo.html)

Adams V-902; Berlin Kat. 1798; Cicognara 696; Essling 1702; Fowler 393; Harvard/Mortimer Italian 543; Millard Italian 156; Norman 2157; Sander 7694.

Other Books

GHEZZI, Giuseppe

Roma tutrice delle belle arti, pittura, scultura, e architettura – mostrata nel Campidoglio dall'Accademia del disegno il dí 2. Ottobre 1710. Essendo...

€ 700

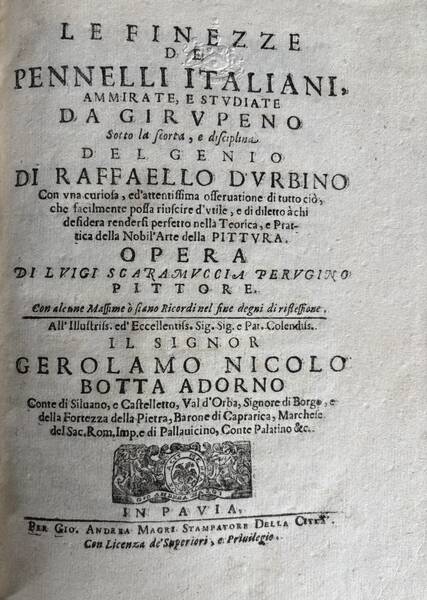

SCARAMUCCIA, Luigi

Le finezze de pennelli italiani, ammirate, e studiate da Girupeno sotto la scorta, e disciplina del genio di Raffaello d'Urbino : con una curiosa,...

€ 1.200

SANDRART, Joachim von

Romae antiquæ et novæ theatrum; sive, genuina ac vera urbis, juxta varios ejusdem status, delineatio topographica.

SOLD OUT

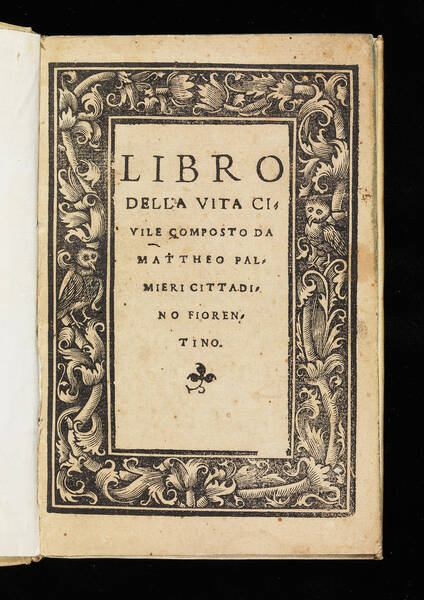

PALMIERI, Matteo

Libro della vita civile composta da Mattheo Palmieri cittadino fiorentino.

SOLD OUT

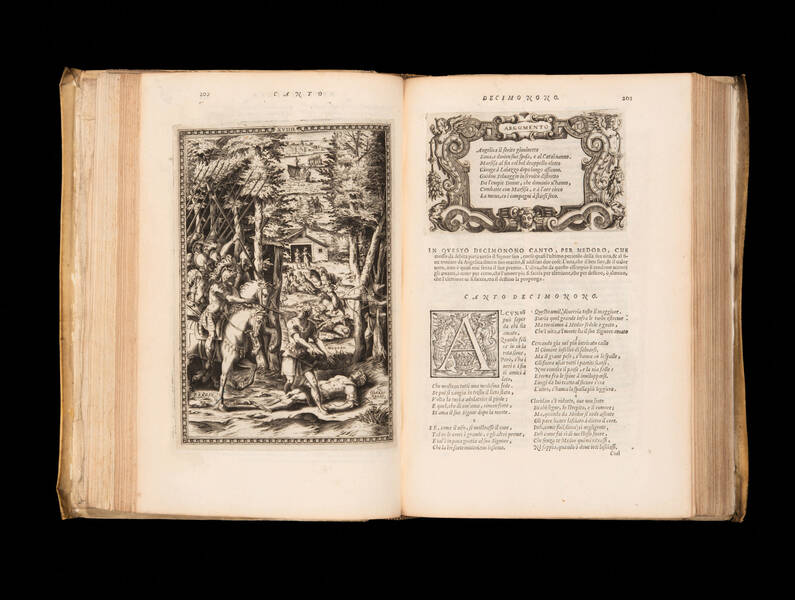

ARIOSTO, Ludovico

Orlando furioso di m. Lodouico Ariosto nuouamente adornato di figure di rame da Girolamo Porro padouano et di altre cose che saranno notate nella...

SOLD OUT

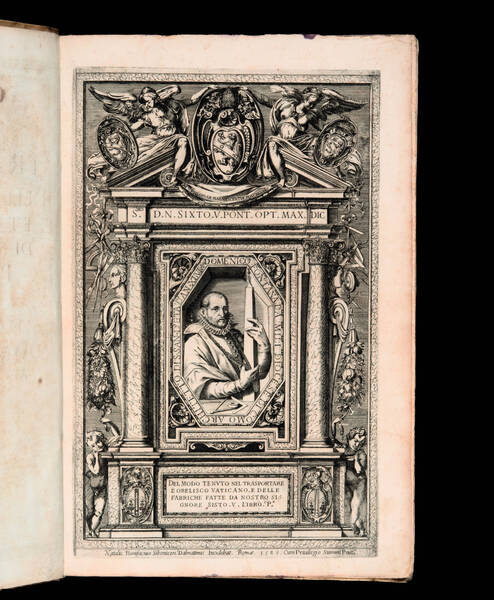

FONTANA, Domenico

Della trasportatione dell'obelisco vaticano et delle fabriche di nostro signore papa Sisto V fatte dal cauallier Domenico Fontana architetto di sua...

SOLD OUT

BARBAULT, Jean

Les plus beaux monuments de Rome ancienne.– Les plus beaux edifices de Rome moderne.

SOLD OUT![La zucca del Doni. [Fiori della zucca del Doni; Foglie della zucca del Doni; Frutti della zucca del Doni.] La zucca del Doni. [Fiori della zucca del Doni; Foglie della zucca del Doni; Frutti della zucca del Doni.]](https://www.medariquier.com/typo3temp/pics/efd2a7667b.jpg)

DONI, Anton Francesco

La zucca del Doni. [Fiori della zucca del Doni; Foglie della zucca del Doni; Frutti della zucca del Doni.]

€ 7.000![Trattato della natura de’ cibi et del bere [...] nel quale non solo tutte le virtù, & i vitij di quelli minutamente si palesano; ma anco i rimedij per correggere i loro difetti copiosamente s’insegnano. Trattato della natura de’ cibi et del bere [...] nel quale non solo tutte le virtù, & i vitij di quelli minutamente si palesano; ma anco i rimedij per correggere i loro difetti copiosamente s’insegnano.](https://www.medariquier.com/typo3temp/pics/d4e0248596.jpeg)

PISANELLI, Baldassarre

Trattato della natura de’ cibi et del bere [...] nel quale non solo tutte le virtù, & i vitij di quelli minutamente si palesano; ma anco i rimedij...

SOLD OUTMEDA RIQUIER rare books ltd.

4 Bury Street St James's

SW1Y 6AB London

Phone +44 (0) 7770457377

info@medariquier.com

![[De Architectura libri decem], M. Vitruuius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula vt iam legi et intelligi possit. [De Architectura libri decem], M. Vitruuius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula vt iam legi et intelligi possit.](https://www.medariquier.com/typo3temp/pics/435a87cdc1.jpg)

![[De Architectura libri decem], M. Vitruuius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula vt iam legi et intelligi possit. [De Architectura libri decem], M. Vitruuius per Iocundum solito castigatior factus cum figuris et tabula vt iam legi et intelligi possit.](https://www.medariquier.com/typo3temp/pics/cb2138da23.jpg)

![[The Commentaries.] C. Julii Cæsaris Quae Extant. Accuratissimè cum Libris Editis & MSS optimis Collata, Recognita & Correcta. Accesserunt Annotationes Samuelis Clarke. S.T.P. Item Indices Locorum, Rerumque & Verborum Utilissimæ. Tabulis Æneis Ornata. [The Commentaries.] C. Julii Cæsaris Quae Extant. Accuratissimè cum Libris Editis & MSS optimis Collata, Recognita & Correcta. Accesserunt Annotationes Samuelis Clarke. S.T.P. Item Indices Locorum, Rerumque & Verborum Utilissimæ. Tabulis Æneis Ornata.](https://www.medariquier.com/typo3temp/pics/e0a4828aa4.jpeg)