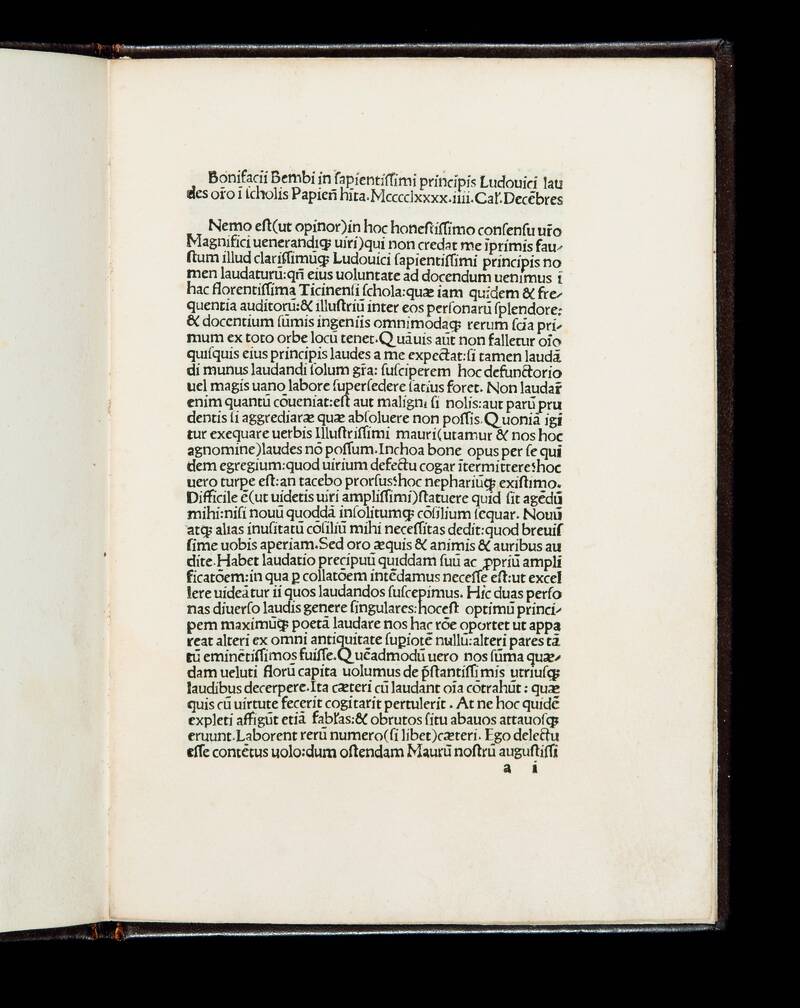

BEMBO, Bonifacio.. In sapientissimi principis Ludovici laudes or(ati)o i(n) scholis Papien(sibus) h(ab)ita.

[Milan: Leonard Pachel], not before November 28, 1490., , 1490Quarto, 4 unn. ll. Roman character. 36 lines a page. A very good copy in a modern morocco binding.

Only edition of this eulogy. Bonifacio Bembo, whose dates are unknown, was possibly a professor of rhetorics, a citizen of Brescia even though he mentions his Cremonese origin. In 1489 he was the co-author of a miscellany published in the honor of Gian Galeazzo Maria, the nephew of Ludovico and formally the Duke in charge. This contribution procured him a chair as a professor of rhetorics at the University of Pavia, upon invitation of the same Ludovico, after consultation with Giorgio Merula, a prominent philologist and historian. Before he had been the principal of a school in Paisolo near Venice. Shortly thereafter he moved to Rome, where he published in 1493 a synopsis of biographies of Nerva and Trajan drawn essentially from Dio Cassius. He should not be confused with his namesake Bonifacio Bembo, a painter of some renown and possibly a member of the same family. Bembo died apparently after 1495. Despite the paucity of his publications (many remained in manuscript) Bembo had acquired some fame especially in the circles of Venetian humanists, where especially Gasparino Borgo and Cassandra Fedele counted among his friends. The characters used indicate Leonard Pachel as a printer. Pachel worked independently from 1488 to 1511, This tract shows Ludovico in his different abilities, as a maecenas, as a politician, as a military man and as a cultivated prince. In fact Ludovico was able to discuss appointments to University of Pavia on a foot of equality with incumbents of the different disciplines, as mentioned in the tract. This sort of maecenatism seldom occurs and is anyway in contrast with more modern forms, where newcomers are co-opted without direct influence of the donors. Ludovico was a cultured prince and also his court at Milan was visited by several poets and historians. As a politician, he is compared by Bembo to nobody less than Aeneas, the founder of Roman might, and this is not without reason as he was defined ‘'the arbiter of Italy'' at the top of his power. The numerous military constructions Ludovico had made build in order to keep at bay the potentially hostile neighboring Italian states deserve another comparison, where Ludovico is compared to Hercules for his ability to reinforce the State and to Pythagoras for the profound science and cunning he did it with; Bembo attacks also the absenteeist policies of Gian Galeazzo Maria. Those fortifications did not though avoid the French invasions of 1498 and 1499, which resulted in the capture of Ludovico and his detention in France. One of the interesting features of this tract is the allusion to the nickname of Ludovico, which later on became of general use and made its way to history textbooks. Ludovico was called ‘'Moro'' (Moor) because of his swarthy complexion, unusual in Northern Italy. The style of Bembo reminds rather Quintilian than Seneca or Cicero, making use of shorter sentences, rich in concepts, and scant use of subordinates. His style reminds of Lorenzo Valla and is in sharp contrast with the Ciceronian style of Southern Italian humanists, such as Matteo Collazio from Sicily, who polemized with Bembo in the occasion of his celebrative writings.

BM XIV century VI, 779; BN (Catalogue des incunables) B-206; Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke 3809; Hain-Copinger-Reichling 2764; ISTC ib00303800; Pelléchet 2032; IBE (Incunables in Spanish libraries) 889; Indice Generale degli Incunaboli 1449; SI 611; Sallander 1608; Proctor 5988.